Lost: One Gospel Message

Has Christianity lost its way? It seems to me, from the memes and articles I see on the internet satirising Christianity, that something has gone badly wrong in the way that evangelists try to teach the gospel message.

Of course, there are plenty of reasons why many people are not Christians. One of the biggest is that God’s existence cannot be scientifically proved. After all, if God exists, then He is everywhere, so He is not an object in the universe that anyone can point to. We can test the effectiveness of a vaccine or a drug by measuring the health of a group of people who have been given it compared to a control group who haven’t. But we can’t test the effectiveness of prayer – or the validity of different religions – by comparing the recovery of one group of patients who have been prayed for by a vicar, one group who have been prayed for by an imam, and a third group who have not been prayed for, because God is perfectly capable of choosing to heal anyone, whether they have been prayed for or not.

But this is a

subject for a different essay. Here, I

want to discuss the way the gospel message is presented.

Yesterday, I had a question on Quora:

I wrote a fairly long answer, beginning ‘For many people, this is why they don’t believe that God exists.

For me, this is why I don’t believe that limited atonement is true.’

Several other

Christians wrote encouraging answers assuring the original poster that God

doesn’t work like this. But one answer I

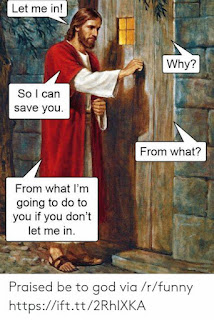

noticed was a page of memes attacking Christianity, including this one:

Now this is a thought that I have had myself, when I was going through a phase of suspecting that there was a hidden message of the gospel that was the opposite of everything Christians believed, and that Jesus had never really intended to save anyone. After all, if the purpose of Jesus’s death was to ‘pay the price’ for our sins, then doesn’t rising from the dead remove the payment? In the courtroom analogy that preachers sometimes use – you are convicted of a crime, the judge has no choice but to sentence you to a fine that he knows you can’t pay, but then he writes you a cheque for the money you owe – doesn’t the Resurrection equate to tearing up the cheque?

Or to put it

another way: if the penalty each of us owes is to suffer in hell for all

eternity, does that mean that Jesus being temporarily dead buys some temporary

remission that is shared out? The Bible

says that Jesus died at 3pm on Friday afternoon, and that his women friends

came to visit his tomb very early on Sunday morning and discovered that he had

been miraculously raised to life. So let’s

say, for the sake of argument, that Jesus was dead for 36 hours, from 3pm on

Friday to 3am on Sunday.

In this case, if the Calvinist doctrine of ‘limited atonement’ – the idea that Jesus did not come, as he said, to save the world and draw all people to himself, but only to save chosen few whom God had predestined to be saved – is true, then, if Jesus had died for just twelve people (say, the apostles apart from Judas Iscariot, and his mother), then each of them could gain three hours’ remission from torment. Or if we take the references in Revelation to 144,000 people with Jesus’s and the Father’s name written on their foreheads to mean that only 144,000 people (of whom, seemingly, only celibate Jewish men are eligible) are saved, then they would each get barely over one second’s remission.

Of course, this isn’t what the Bible says. The Book of Revelation is a poetic allegory, not a literal prediction of the details of the end of the world, and the author just really likes multiples of 12 or 7, but even if we did take it literally, the description in Chapter 7 of 144,000 people is followed by a passage about ‘a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language,’ all of whom are blessed by God so that ‘Never again will they hunger; never again will they thirst. The sun will not beat down on them, nor any scorching heat.’ And the author doesn’t even say that only these specific people, the martyrs ‘who have come out of the great tribulation,’ are the only people to be saved – only that at least a countless multitude including people from every culture on Earth are saved.

So what PDB11 often refers to as the ‘cosmic fixed penalty ticket’ model of atonement doesn’t

work from this point of view, that Jesus being temporarily dead is enough to

pay the price that would otherwise have required all of us to suffer forever. But also, as he frequently says, it doesn’t

work in terms of explaining why we would deserve to suffer forever anyway. How could the finite number of sins that any

one human could commit over a lifetime be sufficient to deserve infinite

punishment?

You can try to

explain these away in terms of infinities: God is infinitely important,

therefore any sin, being an offence against Him, is infinitely bad; and Jesus

is God, therefore his death was an infinitely vast price to pay. But once you start talking in terms of

infinities, you are discussing unknowns that don’t really belong to the realm

of human logic, so it simply isn’t a helpful way to explain atonement.

The gospel

message as presented to a lot of people today looks roughly like this: ‘God

holds everyone to an impossibly high standard of perfection, and justice

requires that He has to punish someone for it by torturing them forever and

ever. Yet the demands of justice

apparently don’t care if He punishes someone who is actually guilty. So because God was born as a human and got

punished instead of you, the good news is that you can be spared being tortured

forever and ever – provided you

believe everything in the Bible, even the bits that contradict other bits or

are contradicted by scientific evidence, and do everything that is in the

Bible, even the bits that logic or your conscience tells you are wrong, and

basically just give up your own freedom of thought and devote your entire life

to trying to meet the demands of an arbitrary and confusing book.’

Or, as another meme puts it:

Not

surprisingly, most people today don’t find this an appealing offer. And I don’t believe that most people in the 1st

century would have done either. If the

deal offered by evangelists had been basically this, but with the added

disadvantage of being persecuted for following an illegal religion, I can’t

believe many people would have received the message with joy and excitement.

It isn’t as if

people prior to Jesus’s coming had grown up expecting to be tormented in hell

unless they could somehow be pardoned.

For much of Biblical history, most Jews hadn’t even believed in life

after death, certainly not an afterlife involving reward or punishment, but

simply that everyone goes down to the grave – hence psalms where the poet

pleads with God to save his life because, after all, he can’t worship God if he’s dead, can he? The writer of Ecclesiastes seemed to be

aware of theories that the human spirit rises upward, unlike that of other

animals, but to be sceptical about this: ‘Who knows if the human spirit rises upward and if the spirit of the animal goes down into the earth?’

In Jesus’s time,

some theological schools of Judaism still didn’t believe in life after death,

since it isn’t mentioned in the Torah.

Others believed, as did some other religious and philosophical movements

around the Mediterranean world, that there was some sort of judgement and

division after death. After all, when

this world is so manifestly unjust, how could a just God not make restitution

after death, rewarding virtuous people who have suffered in this life, and punishing

cruel and powerful people who have seemingly got away with their crimes?

But this doesn’t

mean that most people believed that they and their friends and families all deserved

to be thrown into a fiery furnace and tortured forever, simply for being

normal, imperfect human beings. And they

had no particular reason to believe a preacher who suddenly came along and

announced that they did. They weren’t

children who automatically believed everything they were told. Everyone, Jews or Gentiles, had grown up in

the complex, multi-cultural world of the Roman Empire, and knew that there were

lots of different ideas around.

So, what was the

gospel message? If it comes to that, was

the message that Jesus himself preached in his lifetime significantly different

from the message that his disciples preached after the Holy Spirit came upon

them? And if so, does that mean that his

disciples distorted his true message, or simply that Jesus’s death and

resurrection had changed the situation, so that the same rules no longer

applied? Do we know whether the things

Jesus is reported as having said in the gospels were what he actually said?

There is a lot

to explore here, and, 2000 years on, we aren’t in a position to know for

certain. But what the Bible does tell us

is that the first ever Christian sermon focused not on the Crucifixion as means of atonement for our sins, nor on

recounting Jesus’s commands, but on the Resurrection, and on the gift of the

Holy Spirit. Nobody was impressed by the

Crucifixion – Romans crucified people all the time. What was important was that God had vindicated

Jesus by raising him to life and exalting him to sit at God’s right hand (the

idea that Jesus actually was God didn’t

seem to be important to the first Christians), and that the Holy Spirit was

changing people’s lives.

Yes, Christians

in the early church believed that the Crucifixion was important, and that Jesus

had atoned for our sin. But they didn’t

assume that there was only one acceptable explanation – penal substitution –

for how this worked. They were just satisfied that, somehow, it

did.

As Steve Chalke

says in his book The Lost Message of Jesus, the evangelical fixation on the Crucifixion meant that, when preaching as

a church minister, he even found it problematic to teach about Easter, because ‘The

cross had become, not just central to the gospel, it had become the whole

gospel.’ The Resurrection had come to

seem an irrelevance.

When I first

read this book, a few years ago, I was surprised at how mainstream its theology

seemed, when I had expected a book called The

Lost Message of Jesus to teach something far weirder and more contrary to

2000 years of Christian belief. I was

even more surprised, when trying to look up the above quote on a search engine

just now, to find that almost all the hits I got were from evangelical websites

attacking Chalke as a heretic.

For Lent, I

think it is time to re-read The Lost

Message of Jesus, and also some more academic discussions of atonement,

like Past Event and Present Salvation: The Christian Idea of Atonement by Paul S. Fiddes. And it is certainly

time to think some more for myself about what the gospel message is, and how it

has become so badly distorted.

Comments

Post a Comment