Thinking of Myself, More or Less

While tidying my desk for Christmas (okay, trying to clear some of the mess of papers off my desk for the first time in years, and finding all sorts of letters I hadn’t responded to or hadn’t even noticed or opened, including letters telling me to make medical appointments, and personal letters from friends who are now dead and whom I can never respond to), I found something triggering.

I know people

overuse the word ‘triggering’ a lot, to refer to anything that annoys

them. However, this really was a

reminder of trauma which caused me to relive the trauma to some degree. Specifically, it was a handout from my

therapist, which reminded me of a session which had gone horribly wrong and

which was one of the reasons that I no longer go to therapy.

I had been

telling her about an insight I had had which was important to me. I can’t remember precisely what I told

her. Maybe it was the realisation that

the cute sayings we get taught in Sunday school like ‘The key to JOY is to put Jesus first, Others

next, and Yourself last,’ (with the

implication that we shouldn’t think about meeting our own needs until we have

met the needs of all the other 8 billion people on the planet) are misleading.

I had realised

that the Bible says, ‘Love your neighbour as yourself,’ not, ‘Love your neighbour instead of

yourself,’ or ‘Love your neighbour more than yourself.’

As a child, I

had gained the impression that as Christians, we were supposed to hate ourselves. When I had asked my Sunday school teacher

what it meant to love our neighbours as ourselves if it was wrong to love

ourselves, the teacher had explained that it meant, ‘Love your neighbour the

way you used to love yourself before you became a Christian and repented of

self-love.’

Later, I had

wondered whether the teaching of Jesus and many other first-century rabbis that the first and greatest commandment is ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength,’

and the second is ‘Love your neighbour

as yourself,’ meant in practice that we should be so obsessed with worshipping

God that we have no time or energy left for loving ourselves or other people.

But PDB11 had pointed out to me that when Jesus was asked what sort of neighbours we are

called to love, he illustrated what loving your neighbour means by telling a

story of a man going to great lengths to care for an injured stranger. So if God wants us to care for other

people like this, presumably He also wants us to care for ourselves.

What is easy to

overlook, when we treat commandments like ‘Love God,’ and ‘Love your neighbour,’

as arbitrary rules, is that the central message of Christianity is that God is love. The expectation is that if we know how

much God loves us, we will love God, and that if we know how much God loves

everyone, we will love the people around us as He does - and, by the same

token, that if we know how much God loves us, we will love ourselves as He

loves us.

Anyway, I can’t

remember what I said, but I think it was something on this topic. And my therapist suggested, ‘Here’s a saying

which may be helpful to you: “Humility is not thinking less of ourselves, but

thinking of ourselves less.”’

I was quite

worried by the implications of that, and asked her, in an increasingly agitated

way, what she meant by it. After all,

she and I were both Christians, so we presumably both agreed that humility was

a virtue which we should be cultivating.

So, I asked, if ‘thinking of ourselves less,’ was what we needed to do

in order to be properly humble, didn’t this mean that I shouldn’t be seeking to meet my own needs (such as improving my

mental health), nor trying to understand my own thought processes better? Was this what she thought, I asked? If so, should I be in therapy? If this was what she believed, why was she a

therapist? What was she aiming to

achieve?

The therapist,

seeing that she had upset me, tried to calm the situation down by

disengaging. This wasn’t about her, she

said. This wasn’t about her beliefs or

values. She had given me a saying for my

consideration, but it would be inappropriate and unprofessional for her to

discuss what she meant by it or whether she believed the same things that I

thought it meant, and now we should just move on with the session.

This encounter

illustrates several sides of why therapy doesn’t work for me. Firstly, I need to know whether I can trust

my therapist, and to know that, I need to have some idea of their own beliefs

and values. The trouble is that therapy,

even from Christians, is supposed to be completely non-judgemental or

values-neutral – or rather, it is supposed to appear to be completely non-judgemental and values neutral.

In practice,

everyone has values, and these values guide the choices we make in life. If someone decides to become a psychotherapist,

it is presumably because they want to help people recover from mental illness –

and for this to work, they depend on their patients also wanting to recover. If they decide to work in talking therapy,

rather than, for example, trying to train people to conform to social norms by

means of rewards and punishments, it is presumably because they believe that

understanding our own thought processes better is the key to improved mental

health, and that this is a good thing.

However, they

aren’t allowed to say this directly

to someone who directly asks them whether this is what they believe. They just expect it to be implicit. And this is the second problem: for an

autistic person like me, nothing is obvious about other people’s motives without

being specifically stated.

The third

problem is that if I ask a direct question like, ‘Do you believe that it is

right or wrong to think about ourselves?’ and don’t get a direct answer, then I

can’t simply forget it and move on. I am

still stuck on this point. Admittedly,

if I am very upset, I may not understand or not believe an answer if I do get

one, and may just shout, ‘You don’t mean that!

You can’t, because it contradicts what you said just now!’ – but all the

same, there needs to be an

answer. If the other person doesn’t answer, then that just implies

that they have something to hide, and that the true answer confirms my worst

fears.

So, perhaps in

that session or perhaps in a subsequent one, the therapist gave me a piece of

paper. Perhaps she may have offered it

to me in that session and I angrily refused it, but then apologised and asked

for it at the next session and kept it.

I can’t remember the details.

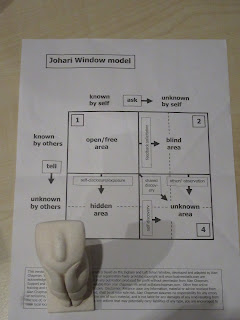

The paper showed

the Johari Window model. This pictures our lives as divided

into four quadrants: the aspects of our personality that are obvious to

ourselves and to everyone else; the things that other people can see about us

but that we can’t see about ourselves; the things that we know about ourselves

but don’t dare tell other people; and the things that we can’t let other people

know about us because we ourselves don’t know.

I know she was

trying to be helpful. Perhaps she

thought that, being autistic, I would find a picture or a diagram easier to

understand than a verbal explanation.

(In some circumstances, this is true: for example, I can understand how

to get to somewhere much more easily by following a map than by reading a walking

guide.) Perhaps she thought that having

something I could take home and look at would be less stressful than trying to

discuss issues during a therapy session.

What she couldn’t

understand was that it wasn’t any help to me without her personal reassurance

that yes, she believed that seeking to understand myself better was a good

thing, and not an example of selfishness that I ought to repent of.

At any rate, the

next time PDB11 and I discussed how we were living beyond our income and needed

to make savings somewhere, I decided that therapy was probably the thing I

could most afford to do without. This

was around eight months ago, and I don’t think my mental health has declined

noticeably since I stopped going. If

anything, it may have improved a bit.

The trouble with

therapy is that most of it is intended for normal people with normal

problems. I am not normal, and I don’t

hear things the same way that normal people do. Equally, therapists sometimes don’t hear the

things I say if they aren’t the sort of problem a normal patient would have,

but interpret it as meaning the most similar-sounding thing that a normal

person would say. For example, if I say,

‘I fear that if I’m happy in this life, God will punish me in hell for having experienced

good things in this life,’ a therapist might hear this as, ‘I believe that when

I experience suffering, it is because God is punishing me.’

I don’t want to

give the impression that this therapist was useless. She was much better than most, probably the

best therapist I have ever been to (or perhaps I was just nearer to being ready

to be helped than I was three years ago, or six or eight years ago). Probably around 95% of the time, she was very

helpful. But if things went well for nine

and a half sessions, and then half of one session went downhill because she said

something that upset me and then wouldn’t explain that she hadn’t meant it the

way I had taken it, then that half-session could be enough to undo the damage

of the previous nine and a half sessions and put me back to square one.

Or so it seemed

at the time. Maybe I did make more

progress than I thought. Probably the

progress I have made since then is at least partly the result of her help. But I think I have to accept that I need to

work things out for myself. Therapy isn’t

something we do for an hour once a fortnight with a trained professional. It is something we have to do for ourselves,

in how we talk to ourselves and how we encourage ourselves to think and feel,

every day.

Comments

Post a Comment